Immigrant Theatermakers Take Center Stage at Global Forms

When Rattlestick Theater founded the Global Forms Festival in 2020, immigrant theatermakers were in an impossible position. Widespread theater closures meant they couldn’t work, but not working was in direct violation of their visas. In its first iteration, Global Forms employed 30 international artists, ensuring that creatives from playwrights to actors could continue creating in the United States. Since then, the all-immigrant event has hired 150 artists from 50+ countries, putting their stories center stage in a series of panels, readings, and workshops. The event, which ran this year from June 23 through 29, has become a way to support immigrant theatermakers on all sides, both highlighting their experiences and providing tangible work opportunities.

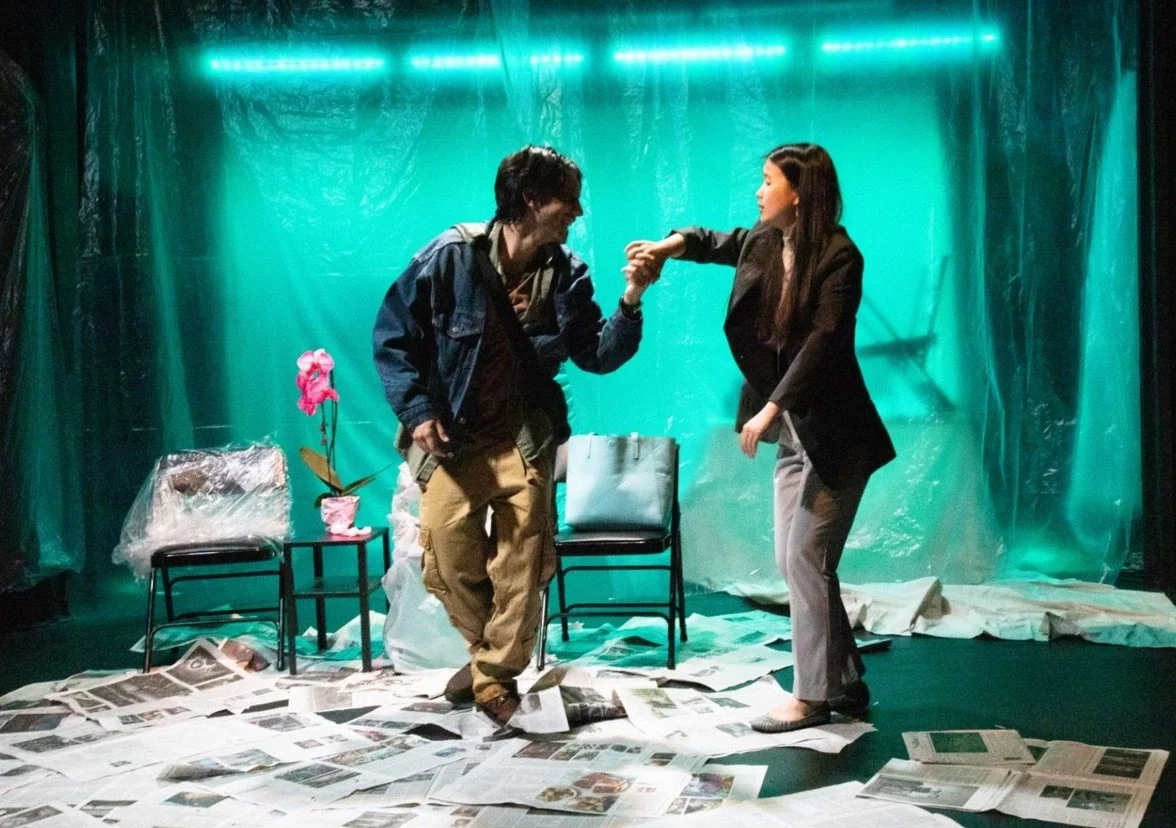

This year, the festival is focusing on going deeper, delving into a single showcase production. Best Foreign, a play by Argentinian writer Francisco Mendoza, tells the story of an Argentinian filmmaker facing a US press campaign that raises questions about American exceptionalism and imperialism. “It’s provocative, it’s political, and it’s not a warm, fuzzy immigration Hallmark story,” says Global Forms curator James Clements, an immigrant theatermaker from Scotland. In this conversation, we discuss Global Forms, Best Foreign, and the challenges of the immigrant theatermaker.

Catherine Sawoski: James, can you tell us a bit about the festival? What inspired its formation, and how does it support immigrant theatermakers?

James Clements: Global Forms was launched back in 2020 at the height of the pandemic as an initiative of Rattlestick Theater. Individuals who are on an artist visa—or any work visa, as the festival’s name suggests—are contingent on work and on being employed. So when everything shut down, immigrant artists faced a dual crisis. One was that, as visa-holding immigrants, you’re not eligible for any unemployment or relief, because that breaches your visa. And two, if you’re not working, your visa breaches. Global Forms was founded on the idea that immigrant artists bring immeasurable value to the American cultural scene and the New York City theater ecosystem specifically. Interested producers thought, can we gather, facilitate, and create space for excellent work by immigrant artists to be spotlit, while also helping those folks do what they have to do to remain here?

CS: What are the challenges the immigrant theatermaker community faces to this day?

JC: In terms of being an immigrant artist, it depends on where you come from. There’s a whole host of linguistic, cultural, and financial components to navigate. Anytime you move to a country and a culture that’s not your own, there’s an element of code switching and translating. Global Forms exists with that same impulse, to create a platform for immigrant artists, but has also grown into this dynamic community engine.

You get someone from Ukraine in the room with someone from India, with someone from Puerto Rico, with someone from Miami, with someone from Scotland, and that's where so much intersectional magic happens. It’s creating a sense of community and a network for folks that left those things behind, and also playing its small part in creating this global, intersectional theater culture.

CS: Francisco, Best Foreign is a semi-autobiographical piece about an Argentinian dramatist who made a film with the same title as one of yours. How is it based on your experiences as an immigrant in the US?

Francisco Mendoza: I moved to the United States in 2015 for an MFA program. I always loved the exciting stories—page turners, sci-fi—I was excited by the magic of storytelling. When I came to the US, it was during a moment when the values of what stories were being told started to shift toward identity-based curation. There was this notion given to me in school that what I can say is where I come from, that no one had time for anything but an elevator pitch, and that my elevator pitch should contain that I’m from Argentina. So, quite often, I would be writing my fantastical, high-concept stories, and professors would ask, Why is this not set in Argentina? Why is it not set in Brazil (where I had lived)? I didn’t understand the question.

It taught me to treat my history as an elevator pitch. I did write a play that tackles the Argentinian dictatorship. The play was successful, and I don’t have regrets over that. But the moment I didn’t need to work on that play anymore, I didn’t. I had nothing to say. I didn’t live through the Argentinian dictatorship, and I’m not an expert on it. The fact that it is a very important part of my country’s history does not imbue me with any sort of expertise to talk about it, regardless of the advice that I’ve been given, regardless of expectations of the industry.

Much later, once I had secured a green card and I felt like I had done what the industry had demanded of me, I started reflecting on this, and out of that came this new play that asked whether that process—that shrinking of one’s identity into a box that can be packaged and sold—has any effect on society and the pursuit of happiness. Best Foreign was one of the first plays I wrote without outlining first. It just poured out of me.

CS: In addition to your writing, you also co-founded the Immigrant Theatermakers Advocates. What were the experiences that inspired this and how have you seen it make an impact?

FM: As James mentioned, the pandemic was a tough time for immigrants. A few different initiatives [including Rattlestick] came together to protect [us]. I was very happy to see that. Immigration is a conversation that doesn’t have a lot of room in the American theater industry, which can be quite xenophobic in ways that aren’t readily apparent. To give a practical example, up until 2021, anyone who was not at least on a green card could not be part of Actors’ Equity. I understand that that is not initially thought of as a xenophobic policy, but the effects of it end up being xenophobic. I’ve met a lot of folks who have had opportunities revoked or denied precisely because of this policy, even though they were the actors whom production wanted to cast.

Once the immediate emergency [of Covid] ended, some of these initiatives ended as well. I got together with a couple of friends, all at Rattlestick. We got together and asked, What would it look like for us to create something that doesn’t live inside a specific institution, not subject to any changes in budget or institutional priorities? From this, we co-founded The Immigrant Theatermakers Advocates. It has been a joy to see our community coming together. We give advice, we put together lists of lawyers that give our members free consultations, and we keep working on new avenues through which we can advocate and support. It’s a joy to see more and more people joining and having the network of support.

CS: What more can both the New York theater community, and the US at large, do to support immigrant theatermakers?

JC: I think that the New York theater community can do a better job of letting itself be educated and educating itself. Immigrants are self-starters, and we’re used to working twice as hard. All we require from the New York theater community is an understanding of how we need to work, and the space and trust to do so. With knee-jerk [reactions of], “there’s a complicated form” or “this is too confusing,” we encourage folks to take the time to fill that form in. Otherwise, you’re closing our community off to tens of thousands of incredible makers from all over the world.

FM: I feel like Americans often get trapped in thinking that immigration is a one-way phenomenon. The process of immigration to the United States is a living relationship to the outside world—a two-way relationship. I grew up outside of the US, but it was very present in my life. There’s a joke in Argentina that we get up and we check two things: the weather and the dollar exchange rate. [People in the US] ignore how the US went out into the world and created those relationships.

How has the US shown up in the rest of the world, and what relationships has it established there? And how can we, knowing that this is the case, cultivate a responsibility in the way that we treat people who want to come to this country? I feel like that aspect is often ignored in favor of this narrative of “folks want to come here because we did such a good job building this country.”

JC: It’s almost like the same answer on both sides, which ultimately comes down to education and information as a pathway to nuance. [It’s] a more egalitarian ecosystem than a one-way act of charity, which I think is a reductive way to view migration, immigration, those patterns anywhere in the world. Nuance. That’s what we need.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

All Global Forms events are free. Reserve tickets here.