Paula Modersohn-Becker Is

In a letter written to the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, German artist Paula Modersohn-Becker wrote: “And now I don’t know how to sign my name. I am not Modersohn and I am not Paula Becker anymore, I am Me, and hope to become that more and more.” In 1906, the German expressionist, still relatively unknown, was both an artist and a wife, something unbelievable during the early 1900s. To say “I am Me” is a clear search for identity outside of the ones assigned to her. It is fitting that New York’s Neue Galerie utilized this statement as their exhibition’s title, as it is the first major retrospective of Paula Modersohn-Becker in the United States. I Am Me is about celebrating Modersohn-Becker’s singularity, desires, and personhood.

The titles of Modersohn-Becker’s works are nothing if not straightforward, telling you exactly what you are looking at. Her portraits are often close-ups. Yet, in all she reveals, there is still a mystery in what is made so explicitly clear. In Nursing Mother In Front Of Birch Forest (1905), one of the first works in the show, we see precisely what the title suggests. But, upon closer look, there is much more. The mother looks down on her child with a gaze of longing and love. The connection between mother and child is so potent and intense, and there is a clear giving and receiving of life.

I linger on the mother’s look. What has always struck me about Modersohn-Becker’s paintings is her willingness to depict women’s vulnerability. Modersohn-Becker paints women as she understands them: pained, fragile, and real. In Nursing Mother, there is so much longing and sadness. In 1905, Modersohn-Becker had not yet given birth, but she possessed a complex understanding of the often private, solitary experience of motherhood. Placing the mother in the birch forest––perhaps a location of seclusion––adds to this sentiment. This moment of exchange is intimate, only shared between mother and child. Modersohn-Becker chooses neutral tones, browns, and yellows, and the environment and mother––two sources of life and existence––become one.

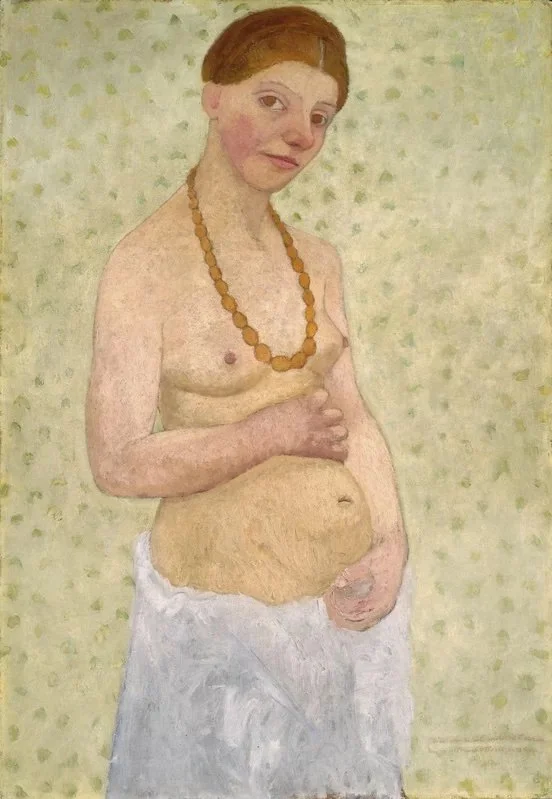

In the final room of I Am Me, it is especially clear that Modersohn-Becker wanted children of her own. In 1906, Modersohn-Becker was 30, and, historically, during the early 1900s, having children when over 30 was considered high-risk. Motherhood, then, feels linked to time, mortality, and selflessness, giving oneself completely to birth a new life. At the center of the room is Self-Portrait on her Sixth Wedding Day (1906). Its intentional placement is striking, as though everything has culminated in this painting. Modersohn-Becker’s desire for motherhood manifests. She stands nude, unprecedented in 1906, and holds her stomach, pointing back to the themes of giving and receiving life in her work. Of all her self-portraits, this also feels like the first where her eyes truly meet the viewer’s. Her gaze remains one of subtle confrontation. Right before painting this portrait, Modersohn-Becker had left her husband, Otto. With this, I think of Marie Darrieussecq describing a portrait of the artist in Being Here Is Everything: The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker: “I try to see where her strength resides. She is staring into space. Open and thoughtful.” Here, Modersohn-Becker is strength, holding herself when nobody else was. However, what is especially interesting about this painting is that Modersohn-Becker was not pregnant when she painted it, but perhaps she welcomes the notion of duality––she could be a mother and an artist.

Self-Portrait With Two Flowers In Her Raised Left Hand (1907) is off to the left. There’s a tenderness as she holds flowers in one hand and her pregnant belly in the other. The pastels possess both richness and lightness, perhaps bringing us toward the intensity of impending motherhood. Moreover, shortly after Modersohn-Becker gave birth to her daughter Mathilde in 1907, she passed away from postpartum embolism at age 31. Since motherhood was a health risk at the time, death and time loomed over her work. In a journal entry from July 1900, Modersohn-Becker wrote, “As I was painting today, some thoughts came to me and I want to write them down for the people I love. I know that I shall not live very long…my life is a celebration, a short, intense celebration.” Her convictions and understanding of her mortality make this self-portrait feel honest, especially knowing this was one of her final works.

Exiting the show, the world feels quiet. It feels like the exhibit was cut short, just like Modersohn-Becker’s life. In the final letter Modersohn-Becker wrote in 1907, she admits, “I’m not afraid of anything, all will be well––except death; that is the only ghost I am afraid of.” Her premonitions stayed with her until the very end but have lingered well past her existence. Modersohn-Becker isn’t a ghost; she’s far more alive than anything spiritual. The words in her diaries and journals are vocal, allowing her paintings to speak. And, as Marie Darrieussecq ends her book, “Paula is here, with her pictures. We are going to see her.” In I Am Me, we are not merely looking at Modersohn-Becker; we are seeing her entirely.

Paula Modersohn-Becker: Ich bin Ich / I Am Me is on view at Neue Galerie New York from June 6 to September 9, 2024.

You Might Also Like:

What Is Fitness Like in a War Zone?

The Beirut Trilogy by Jocelyne Saab

Lost in Time: Serbian Filmmaker Returns to Once-Forgotten Memories